Webinars!

UM Law put on a good one today about Law and Cornavirus. Announced only a few days ago, it drew over 500 viewers. They’re likely to do a sequel. Meanwhile, I gather a recorded version should be online Real Soon Now.™

Webinars!

UM Law put on a good one today about Law and Cornavirus. Announced only a few days ago, it drew over 500 viewers. They’re likely to do a sequel. Meanwhile, I gather a recorded version should be online Real Soon Now.™

No time is a good time to get COVID-19. But if I understood it, the healthdata.org site predicts that in Florida the worst time to get COVID-19 will be about April 15-May 15, in that the demand for ICU beds will outstrip supply in that period. Interestingly, the healthdata.org site doesn’t predict that there will be no hospital beds at all at any point. Of course it’s a big state, so a bed in the Panhandle is of limited use in Miami, or vice versa.

There might, I fear, be another problem with this projection that causes it to understate the problem: a bed is not much use without healthcare workers. I don’t see any sign that these projections take account of the possible toll on doctors, nurses, technicians, and other support personnel in hospitals, although again it’s entirely possible I’m missing something. In some scenarios, the absence of medical professionals due to illness, ill family, childcare needs, or other factors might be a bigger constraint than beds at some critical times.

I’m also not real clear on why this and other estimates put the Florida peak so much later than most other states given that we seem to be ramping up quite quickly. Can anyone explain please?

Christopher Balding, a professor at the HSBC School of Business, Peking University, has a very interesting short paper on “How Fast is Corona Spreading and How Many Undetected Cases Are There?” (alt version: pdf with hyperlinks to references).

It paints a very different picture of the epidemiological numbers than the most widely discussed models do; on the whole, but not in certain parts, this is a more cheerful less dire picture as well.

Prof. Balding slices and dices exposure numbers to conclude that:

From this, he concludes that:

Lastly, he notes “a meta study of corona R0 found a pooled R0 number of 3.32 with a mean of 3.38; probability of being diagnosed correctly with severe symptoms at 0.6, diagnosis probability with mild or asymptomatic at 0.001, and the probability of developing severe symptoms at 0.01; higher transmission from interval between incubation and symptom onset allowing carriers to infect larger number of people.” [R0 is the critical rate of infection number, and is defined as the average number of infections each infected person will cause.]

I have no independent idea if any of Prof. Balding’s numbers are right; I’m not endorsing it, but I found it interesting. An R0 of 3.32 is high, but R0 estimates have been all over the place. And it’s quite a bit higher than WHO’s current estimate! Note that for the 3.32 number to be in the right neighborhood, the lethality also has to be down, otherwise we would have seen a lot more deaths sooner given current estimates of when the infection began.

None of which means, by the way, that the real dangers to sub-populations at risk (e.g. older people), and people in hot spots like New York are any less real. If anything it suggests places can become hotspots pretty quickly.

For those who wish to play with numbers, more data than I can parse can be found at the Worldometer.

Made me smile.

Here.

The New York Times has a report on the failure of a very promising government contract to stock up the national ventilator supply. The deal was sent out for bids in 2008 and awarded to a small company called Newport shortly thereafter. Everything was going great — until it wasn’t.

But it seems to me this story — the product of three reporters on the New York Times (@nkulish @sarahkliff & @jbsgreenberg) — is short on a rather critical fact. See for yourself:

The contract called for Newport to receive $6.1 million upfront, with the expectation that the government would pay millions more as it bought thousands of machines to fortify the stockpile.

Project Aura was Newport’s first job for the federal government. Things moved quickly and smoothly, employees and federal officials said in interviews.

Every three months, officials with the biomedical research agency would visit Newport’s headquarters. Mr. Crawford submitted monthly reports detailing the company’s spending and progress.

The federal officials “would check everything,” he said. “If we said we were buying equipment, they would want to know what it was used for. There were scheduled visits, scheduled requirements and deliverables each month.”

In 2011, Newport shipped three working prototypes from the company’s California plant to Washington for federal officials to review.

Dr. Frieden, who ran the C.D.C. at the time, got a demonstration in a small conference room attached to his office. “I got all excited,” he said. “It was a multiyear effort that had resulted in something that was going to be really useful.”

In April 2012, a senior Health and Human Services official testified before Congress that the program was “on schedule to file for market approval in September 2013.” After that, the machines would go into production.

Then everything changed.

The medical device industry was undergoing rapid consolidation, with one company after another merging with or acquiring other makers. Manufacturers wanted to pitch themselves as one-stop shops for hospitals, which were getting bigger, and that meant offering a broader suite of products. In May 2012, Covidien, a large medical device manufacturer, agreed to buy Newport for just over $100 million.

Covidien — a publicly traded company with sales of $12 billion that year — already sold traditional ventilators, but that was only a small part of its multifaceted businesses. In 2012 alone, Covidien bought five other medical device companies, in addition to Newport.

Newport executives and government officials working on the ventilator contract said they immediately noticed a change when Covidien took over. Developing inexpensive portable ventilators no longer seemed like a top priority.

Newport applied in June 2012 for clearance from the Food and Drug Administration to market the device, but two former federal officials said Covidien had demanded additional funding and a higher sales price for the ventilators. The government gave the company an additional $1.4 million, a drop in the bucket for a company Covidien’s size.

Government officials and executives at rival ventilator companies said they suspected that Covidien had acquired Newport to prevent it from building a cheaper product that would undermine Covidien’s profits from its existing ventilator business.

Some Newport executives who worked on the project were reassigned to other roles. Others decided to leave the company.

“Up until the time the company sold, I was really happy and excited about the project,” said Hong-Lin Du, Newport’s president at the time of its sale. “Then I was assigned to a different job.”

In 2014, with no ventilators having been delivered to the government, Covidien executives told officials at the biomedical research agency that they wanted to get out of the contract, according to three former federal officials. The executives complained that it was not sufficiently profitable for the company.

The government agreed to cancel the contract.

Newport™ HT70 Plus Ventilator sold by Medtronic

But all we get as explanation is this: “The world was focused at the time on the Ebola outbreak in West Africa.” The government was distracted? No one was looking? What does this mean?

Is it too much to hope for a followup story?

Meanwhile, Covidien, which bought Newport, was in turn bought by Medtronic. Medctronic’s web page advertises a Newport™ HT70 Plus Ventilator” which it touts as “Quick to set up, easy to use and durable to withstand rough treatment.” I have no idea how this relates to Project Aura, but I’d sort of like to know that too…

The science fiction writer (and occasional privacy theorist) has a blog called “Contrary Brin” at which he posted Where might this all lead? Unexpected options and outcomes… and some solace. It’s a long post, as many of his are; here’s a quote of just a part of it:

Earlier I made a modest suggestion for what cities across America and the world might do, to maintain some employment and solve real problems, while our streets are mostly empty. The “Pothole Gambit” proposed that we send out scores of 2-person teams to fill potholes, repair empty schools, etc. Risk to the crews would be minimal, if they take basic precautions, and paychecks would flow. This could be done even before testing is widely available.

This kind of selective-contingent thinking leads further to an almost sci fi extension. Once the U.S. has rapid, effective and plentiful COVID-19 tests (as we should and could have had, two months ago) then why not let companies re-open some factories etc., putting back to work employees who have already gone through their exposure to the virus and the following latency period, whether symptomatic or not?

Picture a scenario. Elon Musk rents the Pebble Beach Golf Club in order to test and ease-in staff for his Tesla factory… If that works, expand the experiment. Eventually, some restaurants might even bring in Covid-positive staff to serve an only-Covid-positive clientele.

Sure, one should always look ahead to secondary consequences; would healthy folks in their 20s then deliberately hold COVID Parties, in order to get it over with? I don’t recommend this, as it’s dangerous for the rest of us… and for an unknown few of those youths(!)… that is unless resort hotels rented themselves out to let this happen while young “invulnerables” stay away from their older relatives? (Envision those 1980s “herpes dating clubs.”)

The same sort of thing could happen for Covid-negatives (though only with much better quick-testing.) Companies might wind up having pairs of offices or twin plants engaged in friendly rivalry, like those in that commercial, that produce the left vs. right halves of Twix bars.

Or else trade-off and pick-a-side? Envision Disneyland open for positives and Universal for negatives?

Extrapole some more! “Sectors” of cities divide-up just like in some sci fi flick! (“You’re from ZONE TWO? Get away from me!”) Heck let’s go beyond the obvious Romeo & Juliet riff. Maybe we’ll speciate… !

…no no, forget that last part. Sorry. Professional habit.

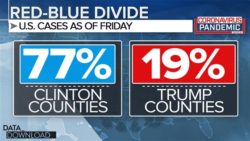

Very funny. But two can play that game: Seems to me, if we’re going to speciate, more likely to be tribal/political. For some time before the current crisis slowed the dating game, we’ve been reading that people don’t date across party lines; given the partisan divide in reactions to COVID-19, it’s hard to see why this won’t make it worse.

Very funny. But two can play that game: Seems to me, if we’re going to speciate, more likely to be tribal/political. For some time before the current crisis slowed the dating game, we’ve been reading that people don’t date across party lines; given the partisan divide in reactions to COVID-19, it’s hard to see why this won’t make it worse.