This got long, so the Florida constitutional amendments will be in Part III. Previously: Some Thoughts about the Downballot (Voters’ Guide Part I: County-Wide Elected Offices).

As long-time readers know, unlike most law professors I know, I support the idea of judicial elections at the state level as a reasonable democratic check on what I believe should be the expansive power of judges to interpret the state and federal constitutions.

As I’ve often said before, if it were up to me, I’d have the executive branch pick judges with legislative confirmation, followed by a California-style retention election every few years in which there would be an up or down vote on the incumbent. If the vote was down, the executive would pick a new judge. It seems to me that the right question is “has this judge done a good (enough) job” — something voters might be able to figure out — rather than asking voters to try to guess from electoral statements which of two or more candidates might be the best judge.

Florida’s system uses appointment plus retention elections for Supreme Court Justices and District Court of Appeal Judges, but not for trial courts. The Governor can appoint judges to fill vacancies between elections, but otherwise those jobs are straight up elected.

This year we have two retention elections for (sadly, manifestly unqualified) Supreme Court Justices, three slots on the 3rd District Court of Appeals, and one County Judge. Both are trial courts, but the County Courts have a more limited jurisdiction.

For the Supreme Court Justices, I will give you my own views, based on reading key decisions and my more than thirty years teaching law. As with the local judges, I do think that there should be a presumption of retention. But that presumption can be overcome for good cause.

For the local races, this year my recommendations are based on:

- My personal view is that I will vote for an incumbent judge unless there’s reason to believe they’re doing a bad job and the challenger would do better.

- After supporting incumbents, my other rule of thumb in sizing up candidates before even getting to the details of biography and practice experience is that in all but the rarest cases of other important life experience we ought to require at least ten years of legal experience from our lawyers before even considering them as judges. Fifteen years is better. I will very rarely support a judicial candidate fewer than ten years out of law school. It just isn’t enough to get the experience and practical wisdom it takes to be a judge.

- I look to see if the candidate filed a voluntary self-disclosure form with the state. Many don’t.

- I’ve become decreasingly reliant on third party sources. I used to rely a lot on the Dade County Bar Association Poll in which lawyers rate the candidates’ qualifications. But the response rate is low enough that I’ve come to wonder about it. Similarly, I’ve soured on the reliability of endorsements. Where once SAVE Dade seemed like a fairly reliable guide, now rebadged as SAVE, it doesn’t seem to me to be as reliable as I used to think it was, in light of a string of, I thought, erroneous endorsements.

- The Miami Herald makes endorsements. In the case of elected officials, I think the decision-makers there are so terrified of annoying establishment candidates that their endorsement only means something if they buck an incumbent. And when did that last happen? But in the case of judicial races, I’ve come to think maybe they do a better job.

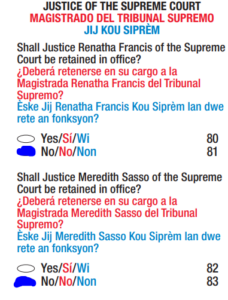

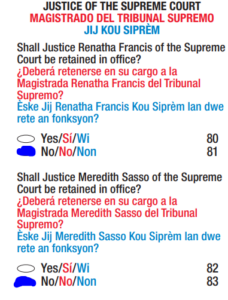

Justices of the Supreme Court

Once upon a time, not so very long ago in fact, the State of Florida had a Supreme Court it could be proud of. I would have easily placed it among the top ten nationally, and you could have made a case for top five. But those days have passed. Mandatory retirement created an opportunity for a near-complete turnover on the court. Quality has suffered. (The FLSCT is also much much more conservative. But that alone is no reason, I think, to vote not to retain a Justice (or a Judge). What matters is the quality of their work.)

This year we’re asked whether to retain Justice Renatha Francis and Justice Meredith Sasso. Both of the Justices up for retention this year are recent appointments by Gov. DeSantis. But even more than his earlier appointments these two Justices cross a line into partisanship that has produced judicial opinions that simply fail to meet a basic threshold of fairness and quality. Neither deserves to be retained.

This year we’re asked whether to retain Justice Renatha Francis and Justice Meredith Sasso. Both of the Justices up for retention this year are recent appointments by Gov. DeSantis. But even more than his earlier appointments these two Justices cross a line into partisanship that has produced judicial opinions that simply fail to meet a basic threshold of fairness and quality. Neither deserves to be retained.

Florida law sets out a process for the approval of ballot provisions seeking to amend the state constitution. In it, the Florida Supreme Courts gets to rule as to whether the amendment is limited to a single subject, and whether its ballot summary is fair or misleading. It does not get to opine on the merits. In the case of the two most contentious proposals this year, Amendment 3 decriminalizing marijuana, and Amendment 4 protecting some rights to abortion, Court majorities (5-2 and 4-3, respectively) approved the proposed summary ballot proposals.

Both Justice Renatha Francis and Justice Meredith Sasso were in the minority both times. In other words, they voted to keep both amendments off the ballot—something devoutly wished by Republicans who feared the inclusion of the amendments would bring Democratic voters to the polls.

What did they say was wrong with the amendments? Brace yourself. (Full text of decisions on Amendment 3 and Amendment 4).

Justice Francis’s dissent called Amendment 4’s summary “overwhelmingly vague and ambiguous,” centering much of her criticism on the term “healthcare provider” a term she claimed would be unclear to voters. Yes, really. [See p. 74.]

And she added that it was “highly unlikely that voters will understand the true ramifications of this amendment” because the “title fails to communicate to the voters that the purpose of the proposed amendment is ending (as opposed to “limiting”) legislative and executive action on abortion, while inviting limitless and protracted litigation in the courts because of its use of vague and undefined terms.” And, “the summary hides the ball as to the chief purpose of the proposed amendment: which, ultimately, is to—for the first time in Florida history—grant an almost unrestricted right to abortion.” [P..53]. Even the conservative majority couldn’t swallow that, holding that “the broad sweep of this proposed amendment is obvious in the language of the summary,” [p.19] and that “[t]he ballot title’s inclusion of the word ‘limit’ is . . . not misleading but accurately explains that the Legislature will retain authority to ‘interfere[] with’ abortions under certain circumstances. [P. 21.]

In addition to suggesting that voters would be fooled, Justice Sasso claimed that despite long-standing precedents to the contrary the Court had a right to object to the content of the proposed amendment: “our review in ballot initiative cases is narrow, [but] this case is different because abortion is different. Dobbs, 597 U.S. at 218 (Syllabus) (“Abortion is different because it destroys what Roe termed ‘potential life’ . . . . None of the other decisions cited by Roe and Casey involved the critical moral question posed by abortion.”).” [P. 59.] I take this to mean that basically no pro-choice amendment would ever pass muster with this Justice. Ever.

I find that outrageous.

Similarly, Justice Sasso claimed that Amendment 4 was “a proposal with no readily discernable meaning.” [P. 66.] To get there, she had to deny that ““viability,” “healthcare provider,” and “patient’s health” all “have clear meanings that are obvious to voters” [P. 74.] but rather “[n]one of those terms have any sort of widely shared meaning.” [P. 74.] Again, even the conservative majority was unpersuaded.

This is, to my eye, results-oriented jurisprudence; when it comes in the context of the constitutional amendment process, it’s particularly inappropriate.

On Amendment 3, Justices Sasso and Francis were the only dissenters.

Justice Sasso complained that the amendment summary said it “allows” state-licensed entities to sell pot, when in fact all it did was remove legal obstacles to future legislation permitting those sales. [P. 43.]

Justice Francis alone agreed with Justice Sasso, but added that she thought Amendment 3 violated the single-subject rule because it not only decriminalized marijuana but also allowed for it to be commercialized (er, isn’t that what happens under capitalism when something is legal?). No one else on the court bought into that.

I could go on, but this post is long enough.

(Incidentally, if you need more reasons to vote against Justice Francis, there are many reasons to think she was never qualified for the job to begin with. Indeed, the Florida Supreme Court found that Gov. DeSantis’s first attempt to appoint her was invalid because she had not been a member of the Florida Bar for the required ten years. Didn’t stop him from trying again once she was. In addition to her lack of legal experience, there is the ethics question….)

These Justices don’t deserve retention. Amazingly even the Miami Herald agrees.

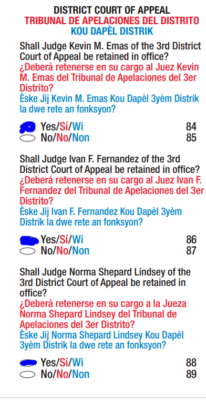

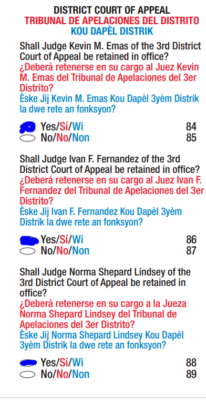

Third DCA

One easy and two less easy ones. The easy one is to retain Judge Kevin Emas (Retain-Line 84). He was appointed by Governor Charlie Crist in 2010, back when Crist was a Republican, so he’s no liberal, but I have no reason to doubt he merits retention.

One easy and two less easy ones. The easy one is to retain Judge Kevin Emas (Retain-Line 84). He was appointed by Governor Charlie Crist in 2010, back when Crist was a Republican, so he’s no liberal, but I have no reason to doubt he merits retention.

As to the others, Judges Ivan Fernandez and Norma Shepard Lindsey, I feel less-well informed. (Incidentally, here’s a nice profile of Judge Fernandez, showcasing his experience on SWAT teams before becoming a lawyer.) Third-party groups break on partisan lines: some local democratic clubs advise against retention; some local far-right groups endorse them (and oppose Emas). Folks I know are a bit all over the map, but I’ve heard nothing specific enough to overcome my presumption that Judges should be retained unless there’s a clear reason not to.

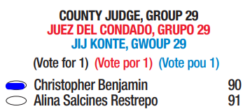

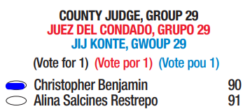

County Court

I like Christopher Benjamin. Here’s a fun profile of Benjamin. Benjamin has been a lawyer for 22 years with quite varied experience (see the profile). FWIW the bar survey had him at 77% of “qualified” or “exceptionally qualified,” while only 57% said the same about his opponent, Alina Restrepo who has 25 years experience in private practice. Over 42% said Restropo was “unqualified”; only 23% rated Benjamin that poorly. That said, the turnout was so low as to make the results rather dubious…

I like Christopher Benjamin. Here’s a fun profile of Benjamin. Benjamin has been a lawyer for 22 years with quite varied experience (see the profile). FWIW the bar survey had him at 77% of “qualified” or “exceptionally qualified,” while only 57% said the same about his opponent, Alina Restrepo who has 25 years experience in private practice. Over 42% said Restropo was “unqualified”; only 23% rated Benjamin that poorly. That said, the turnout was so low as to make the results rather dubious…

Coming up Real Soon Now™ the Constitutional Amendments.