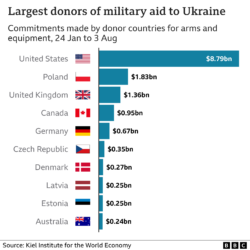

2023 Aid to Ukraine Through Aug 3. This year the US promises about six times more than last year.

There are about 340 million US persons, making each person’s share of the bill for Ukraine aid about $170.41. But maybe you don’t want to count babies? The IRS processes about 169 million income tax returns last year. That makes the individual taxpayer’s share about $360.95. Or, if you prefer, there are 127 million households in the U.S., making each household’s share about $480.31.

Those are numbers I can comprehend. But compared to what? The US federal government spent $6.1 trillion last year, so the Ukraine aid amounts to a tidy 1% of than number. The entire overt US military budget for 2024 is $825 billion, so the Ukraine aid appears substantial–almost 7.4% of the (overt) Pentagon spending (there’s also a large ‘black budget’ that is thought to well exceed $50 billion).

Ukraine aid is also about 50% more than the US spent on agricultural price supports last year. And, although it’s a little harder to calculate, it’s probably about double what the federal government spent on disaster relief.

Working through these numbers didn’t change my view that the aid bill was important and necessary, but it helped me understand this is a genuinely significant commitment (Trump insurance?). As the late Senator Everett Dirksen (really) said, “A billion here, a billion there, and pretty soon you’re talking about real money.”

I wonder how those numbers stack up against the sort of money we were spending to contain the USSR during the Cold War. It would be a fun exercise to pick a year during the Reagan administration and compare the expense on an inflation adjusted basis.

I have no idea how one would separate out funds designs to defend against the USSR from those designed to defend or agress against China and everyone else. Take for example spending on nuclear weapons. How much of that is about the USSR? Or pensions for the armed forces? The mind boggles.

Maybe compare money spent supporting Afghanistan’s defense against the Soviet invasion to the money spent supporting Ukraine’s defense against the Russian invasion. I got the following information and calculations from ChatGPT.

The United States spent approximately $3 billion to $4 billion per year in aid to Afghanistan’s mujahideen fighters who were resisting the Soviet invasion during the 1980s. The total amount spent over the course of the conflict is estimated to be around $10 billion.

The Soviets left Afghanistan in February of 1989. So, I’ll make a comparison from 1988 numbers.

The estimated population of the US in 1988 was 245 million, and there were approximately 92 million households in the US. That comes to $40.82 per person or $108.70 per household. Adjusted for inflation, that comes to $100.48 per person or $267.88 per household.

Frankly, I have yet to hear anyone give a reasoned explanation as to exactly why helping Ukraine is so important. “…but, Putin” is not reasoning.

There was a Colonel in the French army during their Indochina war by the name of Wainwright, I think (he was of English ancestry). In speaking of the French war he noted that Don Quixote tilted at windmills thinking they were giants. The French tilted at windmills, knowing they aren’t giants, but thinking that somebody should be doing it.

It’s pretty much the same here. There is no possible way that Ukraine can “win” this war. They will eventually get beaten down, or it will escalate into something much more terrible that nobody wants. We know this. So we tilt at the windmill, in a half-hearted way, out of some half-hearted idea that it’s our duty to do so, and that that way, one day, we will be able to re-mount our high horse and ride home, held held high.

Alternatively, is all part of the now torn, rotting, and holey pretense that Putin is behind Trump and therefore must be stopped. Trump derangement taken to it’s final limit.

Reason this out, Michael.

Maybe I’m missing something but this seems remarkably uncomplicated.

Unlike Vietnam, we’re supporting a legitimate and popular government which has been invaded in defiance of law and justice. We didn’t connive in deposing a democratically elected leader. We are supporting people (most of whom) hate their invader; the invader is also very cruel. We have not sent troops because our leaders didn’t want to call Putin’s bluff on using nukes, even if only battlefield ones, if we do.

We ran the Afghanistan war through proxies too, but they were much less culturally and ideologically compatible with our values. We only sent troops into the morass as a reprisal for 9/11; whatever the merits of that choice there has been no parallel attack on the US in this conflict. So sending arms is the thing we can do–and maybe instead of dribbling them, we can surge them. I am not persuaded that retaking Crimea is out of reach, although I do agree that both that and even more the Eastern front, looks quite daunting.

The idea that if the Russians gobble up Ukraine they will turn to some combination of Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia next does not seem absurd given the Kaliningrad situation. (The idea that they might attack Finland seems considerably less plausible; the idea that they might attack Poland does seem absurd.)

We have demonstrated we are deterred by Russian nuclear weapons when there is no treaty commitment at stake. While I would say the odds are that Putin won’t test this with a NATO country I am sufficiently doubtful of that prediction as to be willing to pay quite a lot of insurance to avoid the risk. [Corrected last sentence!]

I have never quite understood why the world works this way, but history does teach us, alas, that an unwillingness to follow through on one commitment will be seen by other nations as devaluing the value of other ones regardless of their strategic merit. The rubber meets the road here in the South China Sea, and in Taiwan.

The Chinese regime is at its most dangerous when suffering economic problems; at that point xenophobia and military adventurism seem like useful distractions and ways to maintain popular support. The Chinese economy is in big trouble and faces a real chance of a crash. It has a leader who is in any event ideologically disposed towards pushing on Taiwan. Abandoning Ukraine likely would enter into the calculus of whether to invade Taiwan or to blockade it.

Reasons enough for you?