Does the latest silly PR campaign on Facebook tell us something about changing attitudes towards privacy? The viral campaign is to have women change their 'status' to a color — the color of their bra — ostensibly because this this will 'raise awareness' of breast cancer. I'll leave it to others to dissect the merits of the campaign. (Although this line is pretty good: Telling the world your bra color does not raise awareness of breast cancer. It raises awareness of your bra color.) What interests me is the privacy angle.

In Black and white and red all over – what do those bra-color facebook updates tell us about privacy?, Prof. Wenger argues that the right frame to think about the privacy issue is 'spheres':

A fundamental notion in privacy is the idea of different spheres. This can be described as the classic public/private spheres, …

… I wonder how to analyze the mass voluntary participation of thousands of people engaged in a group sharing of a highly intimate piece of information. This is being done by women, who are particularly vulnerable to privacy attacks (especially relating to their intimate lives). And remember, facebook’s privacy default status is now that updates are open to the world! It’s striking to see crowds happily helping to assemble their own digital dossiers.

Here at the fringes of the public sphere, we're into spheres, but I wonder if that's the very best way to think about it. That said, there's clearly something going on here. As noted by the BBC, How online life distorts privacy rights for all, routinized online disclosure of facts once seen as private can reinforce changing conceptions of what's public and what's private. (Assuming, that is, that people, and especially those now young, continue to collapse the psychological distance between the virtual and real. But, back to the BBC🙂

People who post intimate details about their lives on the internet undermine everybody else's right to privacy, claims an academic.

Dr Kieron O'Hara has called for people to be more aware of the impact on society of what they publish online.

“If you look at privacy in law, one important concept is a reasonable expectation of privacy,” he said.

“As more private lives are exported online, reasonable expectations are diminishing.”

If I were in a quibbling mood, I'd suggest that the online behavior is actually somewhat less significant than this suggests both because I think it reflects something going on anyway out in the regular world (“meetspace” or “meatspace”) and because I think for most people the privacy implications of adding color or phrase in a Facebook listing is much less than it seems.

But I think that the real issue is that this is the wrong tempest in the wrong teapot.

To me the significant aspect about the Facebook incident, and to a large extent the issues that the BBC news story discusses, is that people are posting items about themselves. They control what to release and, initially, where. They decide whether to tell the truth. Is Jane Doe really wearing a chainmail bra? To me, that assertion is much less of a privacy issue than if Richard Roe is secretly photographing Jane with an infrared detector. If Jane is bragging about her SCA chops or perhaps even making it all up, she's in control of her data, at least initially.

True, important issues do arise when the self-reported information is republished, packaged, re-used in ways that Jane doesn't expect (or, worse, had taken reasonable precautions to prevent), and these can be thorny problems. Nevertheless, in a First Amendment world where we protect the right to repeat of the truth, or what in good faith is reasonably believed to be the truth, many of these problems have an easy legal if sometimes uncomfortable social resolution.

No, the issues we should be worried about are involuntary or coerced exposure of personal data, including intimate information, not voluntary clothing self-disclosure. This is especially true in a world in which many people in the US are less in the thrall of nudity or partial nudity taboos than might have been the case fifty years ago (although I suspect there are many variations here by decade and nation), but other people both here and abroad remain very much concerned about body image privacy.

Thus, rather than worry about self-reported textual color information on Facebook, I think privacy scholars and advocates should be thinking hard about a much more important real-world problem: whether the US and other governments are going to mandate digital strip-searches as a condition of air travel. Even if the 'option' of a full-body search exists, few will opt for it because it too is intrusive, and because there's no guarantee it won't be so slow as to result in a missed flight.

Thus, rather than worry about self-reported textual color information on Facebook, I think privacy scholars and advocates should be thinking hard about a much more important real-world problem: whether the US and other governments are going to mandate digital strip-searches as a condition of air travel. Even if the 'option' of a full-body search exists, few will opt for it because it too is intrusive, and because there's no guarantee it won't be so slow as to result in a missed flight.

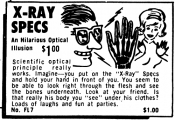

It seems to me that the intrusion into privacy is much more severe for those who experience having some stranger use real-life X-ray specs on them as an invasion of bodily privacy than anything anyone could ever do to themselves on Facebook. How the full-body scanners are implemented will effect the extent of the privacy problem; some have suggested, for example, that the people viewing the images might be off-site somewhere where they would not be able to see the subject of the scan (or, conveniently, vice-versa), and they would text or radio in the all-clear or not depending on what they saw. There are also issues as to what measures will prevent storing the images.

Anything that creates some distance will make linking pictures to people harder, but it won't make it impossible. And of course it is only a matter of time before some enterprising scanning agent figures out how to take pictures of a digitally nude celebrity and sell them to the highest bidder. Entrepreneurs take note: both celebritybodyscan.com and celebrityairportscan.com have already been registered.

We don't yet know the details of how TSA proposes to manage the new scanners, and it is not obvious that TSA will disgorge the information willingly, so it is good to see that the Electronic Privacy Information Center has filed a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit to try to get more information about the program. Unfortunately, I suspect that many of the most interesting parts about how the images will be handled will fall under FOIA exception (b) which protects from disclosure all information “specifically authorized under criteria established by an Executive order to be kept secret in the interest of national defense or foreign policy and …are in fact properly classified pursuant to such Executive order.”

To me, privacy is not primarily about no one knowing things about me. Rather, it is about my ability to control what information I choose to make known about me and to whom, and to some degree to control — or in some circumstances at the very least stay informed — about the further sharing of that information. And that's why digital strip searches, a coerced privacy invasion by the government for what may or may not be a reasonable means to enhance the safety of all air travelers in the wake of the underwear bomber — seems a much bigger deal than self-reported possibly fictional underwear colors.

What I find interesting about this and other viral marketing campaigns is related more to the synchronization of human behavior and the enculturation of certain normative behaviors.

Think about clocks: they are in one respect a way to measure out the day, but in another sense, they are a way for large numbers of humans to synchronize their behavior without having to be in direct communication with oneanother. Can massively-synchronized behaviors such as this be used for indirect purposes?

What sorts of indirect purposes might be the objective of such exercises?

I can think of a few. Many have to do with signal intelligence and automated psychological profiling: FaceBook has a record of everybody made aware of this exercise through FaceBook’s internal messaging systems. Whether one chooses to reveal this information or not provides a psychological insight.

Some have to do with the interests of advertisers: viral marketing is all about getting individuals to perform certain actions, essentially doing the work of advertisers for them. 40 years ago mass marketing campaigns were more effective because there were fewer TV stations and glossy magazines. Today, the advertising market is more fragmented, and the “buzz” created by viral marketing campaigns is a way to get a message out. Exercises that make use of these psychological manipulations ostensibly for purposes of social welfare are a way to sensitize audiences to “opportunities” for engaging in the same behaviors for (somebody else’s) commercial interests. The interest here for advertising supported service is clear where it comes to having an audience more familiar with and willing to participate in such behaviors.

If social custom is actively molded by commercial interests to fit the interests of commerce, and the ubiquity of these social customs puts pressure on people to comply with these customs, is this not a form of coercion?