I run a tough classroom, take attendance. I think of the classroom as a formal place: I wear a tie, and sometimes a jacket (I used to wear suits; I've mellowed along with the times, as today — unlike ten years ago — many of my male colleagues probably teach in open collar; some even in shorts and sandals). I call students by their last names, and although in most upper-level classes I lecture rather than attempt to teach Socratically, I do question aggressively and expect a certain degree of preparation. Pronouns — IMHO one of lawyers' worst enemies — are banned in my classroom. In recent years, though, I have very rarely called on people unless they are on notice or volunteer (I'll return to that issue in a later post). I am told I have a reputation as a hard case. Certainly when I suggest to my students that I'm really just a pussy cat, the reaction — nervous laughter and incomprehension — suggests they don't exactly agree. I would say I'm just being precise and lawyerly, and expecting my students to do the same. They apparently think I'm being tough or even (not too often I hope) mean.

My in-class affect translates into a set of beliefs about my grades: It is a widespread article of faith among the students that I am a tough grader. Indeed, my research assistant, who should know me better than that, told me so several times. So at last I challenged him to go and collect all my grades for the last three years (all professors' grade distributions are public information, available to all students in a book in our library) and compare them to the recommended curve for upper class courses. I told him that if I was noticeably below the curve I'd consider reforming. He took the challenge happily, crunched the numbers…and then told me I didn't really want to see the results. Because, of course, I am in fact something of an easy grader, and have been for all my teaching career.

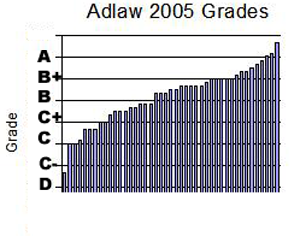

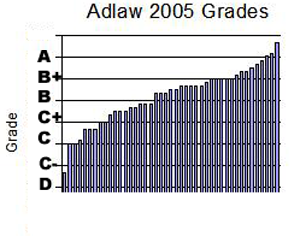

I do try to write exams that will pose challenging problems: working through them is part of the education, after all. But that doesn't mean I expect every student to find every subtlety. Here's this year's grade distribution in administrative law.

(Note that because I give so much credit for class participation, I round the total grade down. Thus, a grade that meets or crosses the B+ line, but doesn't reach the A line is a B+.)

(Note that because I give so much credit for class participation, I round the total grade down. Thus, a grade that meets or crosses the B+ line, but doesn't reach the A line is a B+.)

Of course, it could be that the demeanor frightens people into working harder and this translates into good exams; sitting where I do, there's no way to know. I don't curve, so it's true that on rare occasions there has been a class that did very badly. For example, my first-ever Internet Law class, some ten years ago, was full of people who I think had expected to play computer games all semester (hey, in film and law you watch films, so in Internet and the Law you…) and were appalled to find that they were expected to do legal analysis. But it's hard to believe that these rare cases set a reputation that overwhelms the norm.

Contrast this experience to that of Donna Coker. Donna is an extremely nice person, with a very pleasant demeanor. Donna tells me that she starts off each semester with a little announcement to the class about how she wants the classroom to be a pleasant place, and doesn't think law school needs artificial stress. But she warns students that they shouldn't mistake her classroom style for her grading style: she will be tough on their exams. But, Donna tells me, and encouraged me to blog, the students don't take this in. They believe that because she is laid-back in class, she'll be an easy grader. And by all accounts, Donna runs a friendly classroom. She has a reputation, deservedly, as a very nice teacher. And she grades much tougher than I do.

But just try getting students to believe it.

I don't know why this is. Is it student sexism: a nice woman is surely going to grade more easily than an aggressive guy, right? Or is it just a reflexive form of stereotyping, in which classroom behavior is presumed to translate to grading behavior? You might think it is self-selection, and that the students who couldn't hack it avoid me while still taking Donna's courses (which are either required or on the bar exam); that's plausible, although I'd note that in most years I don't get a lot of the students who get magnas or summas — I think they avoid me to protect their grade averages. Whatever it is, it's very persistent, even in the face of years of evidence.

Update: On reflection, the above account of my teaching style is not as accurate as it could be. It may describe how I taught Civil Procedure, and how I teach Administrative Law (although I'd take issue with the claim that “tough” equals “not fun” — what about all the jokes?), but it certainly doesn't describe my seminars, and actually doesn't describe courses like Jurisprudence or Internet Law particularly well either. Administrative Law is dominated by my perception of a need to cover a certain defined and rather substantial set of material. Leave out any part of the heavily seamed web, and the edifice collapses. Internet Law is different — there's no need to hew to a syllabus: if the class wants to go haring off in an unexpected direction, I'm happy to go there. So in smaller courses and especially in courses with a flexible syllabus, there's much more discussion and the entire atmosphere is much more informal. But I still use last names until after students graduate.

Recent Bluessky Posts

Recent Bluessky Posts

(Note that because I give so much credit for class participation, I round the total grade down. Thus, a grade that meets or crosses the B+ line, but doesn't reach the A line is a B+.)

(Note that because I give so much credit for class participation, I round the total grade down. Thus, a grade that meets or crosses the B+ line, but doesn't reach the A line is a B+.)