It seems to be about 20 years since I started this blog, and more than three months since I last posted anything here, an unusually long gap for me. So I thought I would try to relate some of what I’ve been up to recently. I don’t tend to post about my personal life, but this will be an exception.

Caroline and I celebrated our 34th wedding anniversary in late June in the summer garden spot that is Houston, Texas, a city I had never visited before and did not especially take to–although I was impressed by the extent of the downtown medical center, and by the huge and varied collection of trilobites in the Museum of Natural History. Our actual anniversary day was unpleasant, and not just because it was Houston during a record-breaking heat wave. Rather than a lazy day culminating in a nice night out, I spent a good chunk of the day unconscious due to a knock-out drug administered by a stranger, and embarked on what turned out to be a two-week hospital stay followed by nasty side-effects.

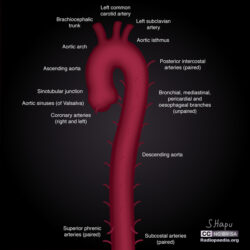

Or, to be more specific, I spent our wedding anniversary on an operating table having an arterial bypass, subclavian to carotid, which means they go into your left shoulder and move stuff out of the way to improve access to the aortic arch. That was just an hors d’oeuvre for the main event, which came three days later: a team of surgeons, led by Dr. Joseph Coselli, split my breastbone open like one might a chicken and rooted around inside me for eight hours in order to repair my aortic arch which had become very bloated. While they were at it, they did a double bypass as well and inserted an “elephant trunk” to enable a likely subsequent surgery on my descending aorta. We’d gone to Houston for the surgery because Dr. Coselli is both pioneer and leading practitioner of the elephant trunk procedure and my doctors thought it certain I would need similar surgery on my descending aorta either very soon or soon. Apparently, my aortic arch has been in a bad way, if nonetheless fairly stable, for several years, but no one told me perhaps because other medical problem crowded it out of the way.

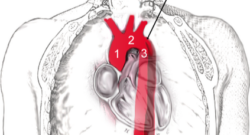

(1) ascending aorta, (2) aortic arch, (3) descending aorta. Copyright © 2016 JHeuser. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0,

Before the surgery, Dr. Coselli estimated that the odds of success were, on paper, just over 90%, a number slightly lowered from the norm by the fact that I had scar tissue in the way from my first open-heart surgery thirteen years ago. Back then I beat the odds when I had an emergency dissection of my aortic valve. (Fifty percent of people whose aorta tears open like this die within an hour or two, and some decent fraction of the others are impaired in various unpleasant ways. Caroline saved me by dragging me to the local emergency room.) Dr. Coselli’s generous 90% estimate was not as reassuring as he no doubt intended it to be, particularly in light of the lengthy consent form I signed that included a page-long list of potential horrible outcomes–although it should be noted that with a surgeon’s self-assurance Dr. Coselli did say he was very confident it would all be fine. Nonetheless, I was glad to have signed a DNR order; I don’t ever want to be Terry Schiavo, and I find the prospect of serious mental impairment even more terrifying than blindness.

I woke up in a big room with bright lights in the ceiling. I was confused. It seemed I was in fact alive, although with the brightness of the lights I briefly considered hallucination as a possibility, but I wasn’t sure what had happened – was this the first operation or the second? Indeed, to this day I still don’t remember much about waking up from the first one, except being moved around the hospital before and afterwards. In the bright room, I had a tube down my throat, but mercifully by the time I was conscious enough to care they took it out reasonably quickly, and assured me that I had survived the main event. I suspect I may have had to be told more than once. Nobody seemed happier about it than the anesthesiologist who had a big smile and said successful outcomes like mine made it all worthwhile. I had to wonder how many of the other sort he experienced. Initially, visiting hours were limited but Caroline made the most of them, despite having to hang around for hours between the sessions.

The operation was not without its side-effects, the two most serious of which were lung-related issues including a horrible painful cough, and what I much later learned my medical chart delicately called “partial paraplegia”. In plain English, I couldn’t stand up, and couldn’t walk, Everyone assured me it was temporary, and indeed by the time I left St. Luke’s to move to a rehab facility, I could stand and travel short distances with a walker—at the price of real exhaustion. Again, Caroline trudged from our hotel to the hospital and back every day, and spent hours with me whether I was awake or asleep, and regardless of how groggy or grumpy I might be.

I’d been to a rehab facility on Miami Beach after the first open heart surgery in 2010 (couldn’t walk for a period after that one either), and had found it to be a really miserable experience. The doctors were mostly absent and somewhat cynical. The nurses were almost without exception burnt-out and unfriendly. The bright spot was the physical therapists, who I saw for a metered hour and half a day. They were cheerful, optimistic, goal-oriented. And thanks to them, by time I went home week later, I could walk a little and, more importantly, drag myself up the stairs to my bedroom once a day.

Fast forward to 2023, and even though people assured me that the staff at St. Luke’s had secured me a place in a great rehab facility just down the street, I was nervous about it. It turned out, however, that the TIRR Memorial Herman really was a nice place, although it was humbling to be one of the least impaired patients in the place—I will never forget seeing a young woman in a motorized wheelchair who had lost both arms at the elbow and both legs at or above the knees. She motored by with a brilliant smile for everyone. Her example ensured that even if I would have wanted to, I would not have dared complain.

Despite the excellence of all levels of staff, it took two more weeks to get me in a shape where I was able to go home, and even then I had to do it in a wheelchair, as I still wasn’t very mobile. My first trip up our stairs took about 15 minutes, resting after every step. Within a week or two I cut it down to five minutes. Now I go up and down at almost normal speed, and more than once a day, although I do feel winded at the top.

The lack of mobility had multiple causes. One thing was my right leg seems to have gotten injured in some way during the surgery, and it still drags to this day, although I’m about to get off the wait list for outpatient rehab here at U.M. Another was that my long struggle with non-Hodgkins large B cell double-hit lymphoma probably left me weaker than might have been ideal for open-heart surgery. And, it turns out that it is hard to relearn to walk when you have trouble with your balance because you have no sensation in your feet—neuropathy being a side-effect of several of the anti-cancer regimes I have enjoyed over the past six-plus years.

On the subject of cancer treatments, although neither R-CHOP with a side of debilitating methotrexate, nor autologous stem cell, nor CAR-T, nor Revlimid worked for me (ok, R-CHOP worked for just over a year, and the Revlimid suppressed the lymphoma but it also increasingly suppressed me), so far it appears that the fifth lymphoma treatment is working. A then-experimental monoclonal antibody mix of Mosunetuzumab and Polatuzumab has given me about a year and a half with “no visible sign of disease”. I’m told by my terrific oncologist, Dr. Alvaro Alencar, that almost all the members of my Phase II study cohort who stayed well this long have so far remained well. If we make it to two years, we get to call it remission. On the negative side, these various treatments aimed at my B-cells pretty much wiped out my immune system. During peak COVID it was actually almost nice that I did not stand out as the world had reorganized itself for my convenience, including remote work and food delivery. But even with the Internet, staying in the house does get old eventually, especially as the world is trying to go back to normal. Whether my immune system too will go back to normal remains uncertain.

The most important point of this medical history digression is that the month we spent in hospitals and rehab in Houston was only the last of a more-than-six-year series of medical adventures, itself on the heels of a thirteen-year-old near-death experience characterized by eleven days of induced coma and a long hospitalization followed by a very long recuperation. In the last six plus years I have had numerous, occasionally long, hospitalizations. And even at home I spent large amounts of time completely out of it, or very much limited in what I could do. This left Caroline to do the worrying, and much of the work, for two—more than two if you consider that the load was aggravated by having to take care of me. Along the way I became convinced that it is often harder to be the caregiver than to be the patient.

I am not one much given to epiphanies. But in the early days after waking up in that bright room, as Caroline held my hand, or just sat nearby, I understood more than ever how fortunate I am to be married to such a wonderful person. I cannot describe what her support has meant, or how grateful I am, or much I love her, so I’m not even going to try. Therein lies the real affair of the heart.

On the gripping hand, having looked at the user’s ORCID record, which is for a Czech masters in economics who did some tutoring several years ago and claims ties to the United Kingdom, Malaysia, Solomon Islands, Georgia, and Armenia but doesn’t seem to publish….I have no idea.

On the gripping hand, having looked at the user’s ORCID record, which is for a Czech masters in economics who did some tutoring several years ago and claims ties to the United Kingdom, Malaysia, Solomon Islands, Georgia, and Armenia but doesn’t seem to publish….I have no idea.